Implement

Implementation advice for developing the talent of high potential and gifted students.

Key action

Implement evidence-based procedures, programs and practices that meet the learning and wellbeing needs of all high potential and gifted students and facilitate talent development.

Differentiated model of giftedness and talent (DMGT 2.0)

The policy aligns with contemporary research in many fields regarding the development of talent. Gagné’s model illustrates the importance of the role educators play. If a high potential or gifted student is underachieving, the model supports teachers to identify the cause of the underachievement. Similarly, the model provides teachers with pathways to support talent development.

Talent development

Watch the video What do we mean by talent development? (3:21)

Speaker

The High Potential and Gifted Education Policy applies to all NSW Department of Education school staff and teachers.

The department is committed to supporting all students to achieve their educational potential.

The policy recognises that high potential and gifted students require evidence-based talent development to optimise their growth and achievement.

So what do we mean by talent development?

Talent development is a deliberate, systematic process or program by which a student's potential is supported in a specific domain such as

- the intellectual,

- creative,

- social-emotional, or

- physical domain.

The goal of talent development is to translate potential into actual performance, so a student is able to achieve personal excellence.

The development of talent however, can be either supported or inhibited by external or internal factors.

Professor Françoys Gagné provides a framework for understanding the "complex choreography" of these internal and external factors necessary to develop talent.

External factors such as teachers, school leaders, learning programs and opportunities can help to foster the development of talent.

Likewise internal factors such as motivation, effort, and learning skills also play an important part in developing talent.

Gagné argues that the development of talent cannot be left to chance, as students, including high potential and gifted students, will not become outstanding achievers by themselves.

This means that :

- families

- educators

- peers

- mentors

- events and/or programs

can play a particularly important role, in supporting talent development for disadvantaged students. These students may not have similar access to opportunities compared to other students.

By deliberately and explicitly supporting talent development for all students, we ensure that students from all backgrounds have the opportunity to achieve their educational potential.

Capitalising on curiosity and interest, ensuring high potential and gifted students are challenged and engaged, as well as supporting wellbeing are all important factors in maximising the development of talent.

By providing optimal learning conditions, teachers and school leaders will make a difference in supporting the development of talent for their high potential and gifted students.

So let's...

find the potential

develop the talent

make the difference.

[End of transcript]

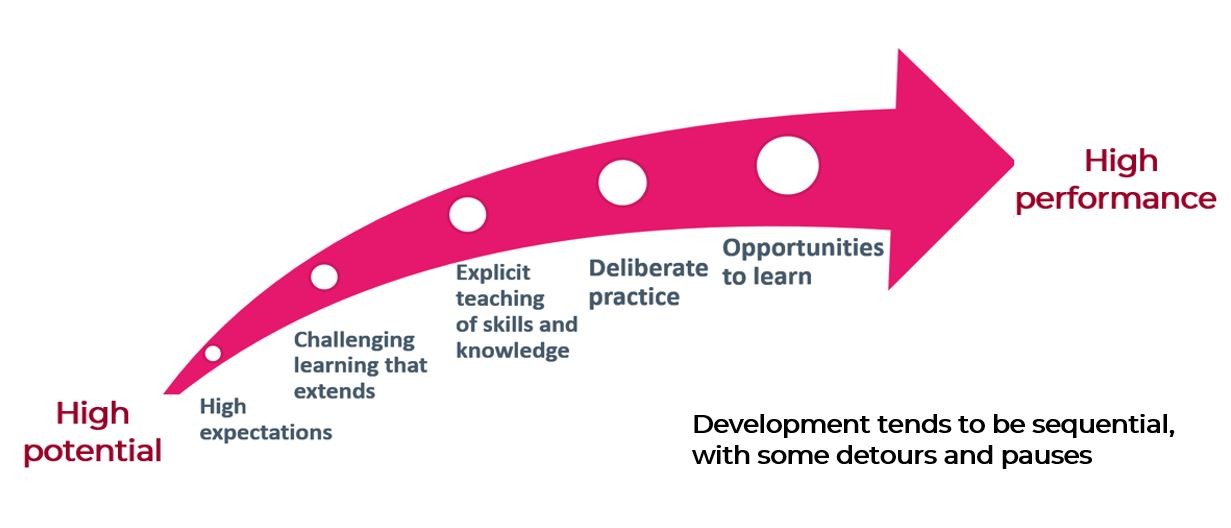

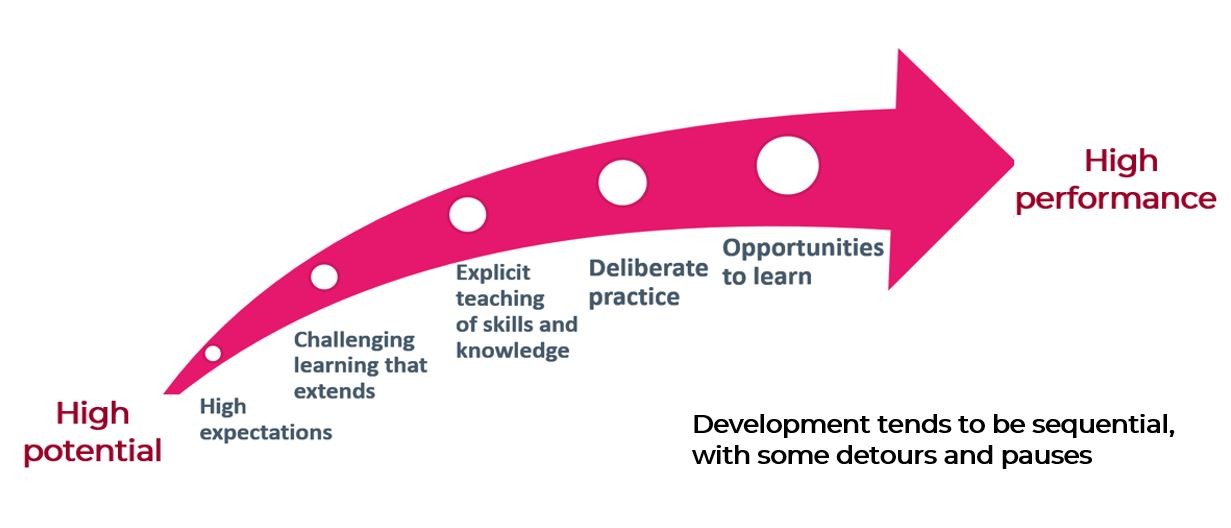

Talent development is the process or program by which a student’s potential is developed into higher achievement in a specific domain or field of endeavour. Students move through various stages of competency along a continuum from novice to competency to mastery. Mastery refers to expertise, exceptional performance, accomplishment or outstanding achievement in a given field, including the accomplished achievement of curriculum outcomes in a subject area or domain. A student demonstrating mastery exhibits a deep understanding that enables them to transfer that understanding across domains.

Factors that facilitate talent development can include:

- opportunities for sustained deliberate practice

- quality teaching, curriculum and provisions including access to flexible curriculum options

- programs that develop resilience, motivation, effort, and perseverance

- provision of a range of opportunities to engage students and identify their learning interests

- a supportive learning environment.

Deliberate talent development programs systematically cultivate the skills and knowledge required for higher performance. Programs should take into account the talent development stage and potential trajectory of the student.

Effective evidence-based talent development programs include:

- differentiation

- grouping for teaching and learning

- enrichment and extra-curricular programs

- advanced learning pathways and acceleration

High potential and gifted students may develop talent and move through the stages of competence more quickly than same-age peers. To develop talent, students need opportunities and encouragement. A student who shows high potential in dance, for example, may never develop a talent without time to practise, space in which to dance and expert support.

Watch the video Developing talent (2:26).

[Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples are advised that this video may contain the images, voices and names of people who have passed away.

Developing talent high potential and gifted education]

[music]

[Jae Jung - Associate Professor, School of Education, UNSW]

Jae

High potential and gifted students exist in multiple domains, so not only in the intellectual domain, but there's also the creative domain, the social domain and the physical domains.

[Sue French - Strategic Project Officer, NSW Dept. Education]

Sue

Those four domains don't exist in isolation from each other. They are highly influenced by each other. But you will see students manifest often in one or more of those domains. What we're saying is that we want students high potential across all the domains to be enhanced, nurtured, supported and developed.

[Ian Barker - Conservatorium High School]

Ian

When students come into year 7 we're looking more for potential than for straight demonstrable ability.

[student singing]

Teacher

Yeah, that’s it.

[Tamara Mitchell - Riverside Girls High School]

Tamara

If we look at, say, a pirouette. The ability to perform the pirouette is based on a student's understanding of balance and their understanding of their own control of their own body. And I'm just there to facilitate the students in their understanding of their own bodies and their own learning in order to continually reach for that extra pirouette.

[James Kozlowski - Endeavour Sports High School]

James

Look I think the key to personal best is setting high expectations. We want our students to achieve at a really high level and then once they've reached that level. Go for something a little bit more.

[Rhianna Kalemen - Canley Vale High School]

Teacher

Today what I want to see

Rhianna

In our curriculum subjects there's that comfort of having the textbook. There's the comfort of I'll highlight this whole passage because that's the answer somewhere in there. Whereas for our high potential students, slowly, we're building a culture where there's this love of learning. This love of action.

[Year 11 Students - Canley Vale High School]

Student A

It really opens up doors. There's so many opportunities that it's... just hop on board

Student B

Hop on board.

[music]

[Find the potential

Develop the talent

Make the difference

Copyright 2019 NSW Department of Education

We acknowledge the contribution of the following groups in developing the policy:

- NSW Primary Principals’ Association

- NSW Secondary Principals’ Council

- The NSW Teachers Federation

- The NSW Aboriginal Education Consultative Group

- The Federation of Parents and Citizens Association of NSW

- The Isolated Children’s Parents Association

- Gifted Learners with Disability Australia

- Gifted Families Support Group

- Academics and consultants from across NSW, Australia and internationally

- Directors of Educational Leadership (DELs)

- Principals

- School leaders and teachers]

[End of transcript]

Creativity and critical thinking

High potential and gifted students require opportunities to engage in creative production. The cultivation of attitudes and mindsets, such as openness and risk-taking with learning, needs to be a deliberate part of programming and quality teaching.

Creativity is the ability to come up with novel and useful ways of doing things. Critical thinking involves learning to develop an argument, use evidence, draw reasoned conclusions and use information to solve problems.

Critical and creative thinking involves students engaging broadly and deeply in their learning using skills, behaviours and dispositions such as reason, logic, resourcefulness, imagination and innovation across all domains of potential.

Differentiation

Differentiation is a targeted process recognising that individuals learn at different rates and in different ways. Differentiation refers to deliberate adjustments to meet the specific learning needs of high potential and gifted students, and may be used in both classrooms and specialist settings. Adjustments may be made to:

- content (what is being taught)

- the learning process (how the instruction is delivered)

- product (the evidence of student learning)

- the learning environment.

Adjustments should be reflected in assessment practices and reporting. Please refer to the suggested strategies for differentiation adjustment tool.

Differentiation Adjustment Tool

The Differentiation Adjustment Tool contains 9 deliberate adjustments to support teachers to meet the specific learning needs of high potential and gifted students. The Differentiation Package (staff only) assists with implementation of the Differentiation Adjustment Tool.

- Complexity poster – Differentiation Adjustment Tool (PDF 95 KB)

- Challenge poster – Differentiation Adjustment Tool (PDF 122 KB)

- Choice poster – Differentiation Adjustment Tool (PDF 101 KB)

- Abstraction poster – Differentiation Adjustment Tool (PDF 85 KB)

- Creative and critical thinking poster – Differentiation Adjustment Tool (PDF 119 KB)

- Higher order thinking poster – Differentiation Adjustment Tool (PDF 129 KB)

- Pace poster – Differentiation Adjustment Tool (PDF 109 KB)

- Authenticity poster – Differentiation Adjustment Tool (PDF 90 KB)

- Learning environment poster – Differentiation Adjustment Tool (PDF 200 KB)

- All posters – Differentiation Adjustment Tool (PDF 776 KB)

Grouping

Grouping students can help teachers to deliberately focus their efforts and supports differentiation. Any group of students will have a broad range of abilities and performance. Improved learning outcomes occur when teachers combine flexible groupings with differentiated teaching and learning approaches.

Streaming, where students are placed in a fixed pathway based on prior achievement, delivers inconsistent learning outcomes.

Grouping practices may vary but they should be purposeful, flexible and equitable, support curriculum differentiation, and be based on formative and diagnostic assessment.

The following considerations are recommended:

- grouping should be deliberate and demonstrate clear purpose which relates to areas of potential.

- grouping requires a degree of flexibility, where students may need to move in or out of a set group throughout the school year. Grouping should not lock students into a pathway which limits future options. Regular reviews of student growth and achievement, as well as options for fluid movement of students depending on task and purpose, can assist.

- grouping practices need to offer differentiation to meet the diverse range of student needs, including high potential and gifted students with disability.

- when grouping is used, it should be employed to facilitate adjustments to the curriculum that support advanced learning.

- wherever possible, grouping practices should be informed by assessments of student learning needs and characteristics. Groups should be created primarily on the basis of ability, mastery, and learning needs.

Grouping strategies may include:

- needs-based or task-oriented grouping: these are temporary groups where students of similar ability or performance are placed together for a particular purpose or task. Students may be grouped and re-grouped depending on learning progress and formative assessment.

- extension groups or classes: students can be grouped for a specific purpose, for example, a public performance. This can be by a cluster or extension group formation, where advanced students are grouped together.

- specialist programs and classes: these include the formal classes and schools administered by the department at a systemic level, for example, sports high schools, performing and creative arts high schools, selective schools and classes. In addition, schools may choose to develop and support their own specialist talent development programs or classes in a specific domain.

- extra-curricular or enrichment groups: these learning programs are designed to extend students by using enrichment strategies that provide greater breadth. At times it may be necessary for students to apply or audition for these programs, for example, for limited places on a sports team or roles in a drama performance. If so, apply the same principles for identification and assessment described above.

Note: Extension class groups should not be advertised or referred to as selective classes or opportunity classes. These terms are used by programs administered by the department’s Selective education Unit.

Extension grouping

Extension deepens student knowledge, understanding and skills, Extension classes offer the opportunity for like-minded, like-ability students to work together on challenging learning or skills development that may not be offered elsewhere.

When schools establish extension groupings, they should create learning environments which are suited to their context. The guiding principles described in the policy should frame the design and the selection process. Even within the extension grouping, there will be a range of abilities so flexible groupings and curriculum differentiation should be considered.

Extension classes may group students:

- by stage, year, composite or multi-age

- on the basis of achievement

- on the basis of potential in a domain.

Groupings should be reviewed at regular intervals. Future placement should not be decided solely by a student’s prior achievement.

Cluster grouping

Cluster grouping establishes a viable group of students requiring additional challenge and extension. Research has shown that cluster grouping can enhance student achievement.

Cluster grouping can help to concentrate differentiation efforts and provide students with opportunities to interact with others of like-mind, interest and ability. In deciding to establish a cluster, consider provisions, programs and administrative requirements.

Enrichment and extra-curricular programs

Enrichment and extra-curricular programs are important components of talent development for high potential and gifted students. Effective enrichment and extra-curricular programs seek to increase the breadth and challenge of learning.

Enrichment and extra-curricular programs need not be specifically designed for high potential and gifted students, but offer excellent opportunities for advanced learning and talent development. For this to occur, there needs to be sufficient scope for students to be challenged.

Schools have a responsibility to support students to access enrichment and extra-curricular programs that meet their specific learning needs. These programs should be sustained, challenging and purposeful. Where possible and practical, this can include quality programs such as:

- student leadership programs including the Student Representative Council

- performing arts initiatives and groups

- school sport teams and coaching programs

- subject-based extension, enrichment and extra-curricular programs.

Early exposure to enrichment is important for younger students to effectively develop talent. Enrichment benefits all students because it:

- improves learning outcomes

- enhances and broadens the curriculum

- is not limited to extracurricular programs

- increases the challenge of learning within the same-year context

- is linked to the curriculum.

Enrichment programs seek to increase the breadth of learning in the curriculum by:

- providing additional learning activities outside of class time that are closely related to the curriculum (e.g. theatre competitions for drama)

- creating cross-curricular learning activities, whereby students broaden their knowledge and skills by combining subject areas (e.g. a cross-KLA project challenge or competition)

- facilitating external modes of learning learning (e.g. art or debating camps).

Advanced learning pathways

Advanced learning pathways, including acceleration, provide flexible responses to students’ identified learning needs. These should be tailored to satisfy the goals identified by the student. Schools should support the participation of students in advanced programs where possible.

Advanced learning pathways offer students learning experiences beyond age-based competency. The term covers a range of learning adjustments such as:

- different forms of acceleration

- mentorships

- cross-school programs

- advanced learning using virtual technology.

High potential and gifted students may need access to advanced learning pathways to ensure that development is commensurate with their ability and specific learning needs.

Acceleration

Acceleration is an advanced learning pathway where students are enrolled in and working towards outcomes beyond their age across domains of potential. Research very strongly supports acceleration as a highly effective strategy for gifted and highly gifted students, and consistently shows positive social outcomes in all forms of acceleration.

To be effective, acceleration must be in a student's best learning interests, the student must want to participate and should be supported by the student’s school and family.

Multiple forms of acceleration exist and can be used individually or together to meet a student’s learning and social needs.

When a student requires academic acceleration, the following may be appropriate:

- early entry to school, a course or year level

- single subject or whole-year acceleration

- the use of multi-age classes

- vertical grouping structures across the school

- flexible groups created for specific subjects or tasks

- advanced learning pathways to access tertiary education.

In other domains of potential, consider the particular needs of the student and provide opportunities, support and flexibility for continued development of their talent and elite performance.

For very highly gifted students, additional acceleration may be necessary as their talents develop.

The acceleration support package

For more detail and comprehensive guidance on the acceleration decision-making process, including specific resources, research and support, explore the acceleration support package.

Learning needs and best interests

Acceleration should be used when it is in the best learning interests of the student. This decision needs to respect the informed views of the parents/carers and the student. It should be based on reliable, valid and appropriate assessment, so that a student’s ability level will be best served through acceleration.

Acceleration options

A range of acceleration options should be discussed and reviewed.

The selected mode should be trialled and evaluated. This can help students find the best fit for their specific learning needs. Trials should not exceed one term and should be followed-up with more substantial changes if successful.

Schools, parent/carers and students need to understand there will be an adjustment period and student transition should be monitored.

Planning

Acceleration should be thoroughly planned and where possible occur at natural transition points, such as the beginning of a school year.

The development of an individual learning plan, in consultation with the student, their parents/carers, the school counsellor/psychologist, teachers, and other experts, can support the process. The plan needs to include specific goals which consider the holistic needs of the student.

The acceleration should be identified, documented, monitored and evaluated.

Support

The student, their parents/carers and the teachers involved must be supported during acceleration. Students may need to be ‘buddied up’, require a transition program, or meet on a regular basis with a mentor. Parents/carers need to be involved in ongoing monitoring of all aspects of their child’s progress through regular communication about identified goals. Information about the acceleration, its organisation and intended outcomes should be provided to students and their parents/carers.

Teachers should be supported by the school’s learning support and/or wellbeing team/s, including the school counsellor/psychologist. Professional learning should be provided for staff.

Curriculum compacting

Once a student’s knowledge and skills are determined through pre-assessment, some elements can be ‘compacted’ so that they are covered in less time or depth. The time saved can then be used for extension or enrichment, or additional revision/support for students who need the extra time.

To compact the curriculum teachers may use these steps:

- Identify clearly the learning outcomes to be achieved.

- Pre-test all students in relation to these outcomes.

- Set a minimum standard of expectation for these outcomes when evaluating the results of the pre-test.

- Identify students who may benefit from curriculum compacting based on the pre-test results and other gathered information.

- Offer these students modified learning, basing decisions on what they have demonstrated they can do and what they are yet to master.

- Offer enrichment and/or extension opportunities once the learning has been achieved to ensure students remain engaged and challenged.

- Offer a variety of choices of differentiated lessons, enrichment or extension opportunities or students may be given the opportunity to direct their own learning.

- Provide regular feedback and ongoing monitoring of student performance in relation to both curriculum outcomes and differentiated outcomes are essential when reporting back to the student and parents/carers.

- Communicate with other teachers when relevant, for example at key transition points.

(Adapted from Reis, S. M., Burns, D.E., and Renzulli, J.S. 1992. Curriculum Compacting: The complete guide to modifying the regular curriculum for high ability students. Mansfield Center, CT: Creative Learning Press)

Mentorships and external partnerships

Mentorships are strongly supported in research for their positive effect on student growth and development. Effective mentorships will look different at different stages in the talent development process of students depending on their trajectory. Departmental policy should guide schools in organising and monitoring mentorships and external partnerships.

High quality mentorships are designed to extend student learning beyond school. These structured mentorships and partnerships may be short or long term. They could include:

- within-school mentorships

- parent and community leaders and experts

- specialists in government, industry and higher education.

Cross-school programs

Schools should work together to share resources to meet the needs of students. For example, where advanced programs can be offered, high potential and gifted students should be given access across school sites. This may occur by participating in person or via online programs.

Virtual and distance education

Where school-based options are not available, students may access advanced learning through distance education. For regional and rural students who meet entry criteria, Aurora College may be an appropriate option.

Representative talent development programs

Opportunities exist where students are selected to participate in a dedicated program for talent development. These talent development programs usually involve learning that is highly advanced and include programs in performing arts, sport, academic areas, creativity, civics and citizenship and leadership. Some representative student programs, such as those offered through the department’s Arts Sports and Initiatives Unit, are examples where students access advanced learning through representation of their school, region or state in teams or ensembles.

Social and emotional development and learning

In order to achieve their best, all students need to be challenged to learn and master new skills and feel a sense of success, wellbeing and belonging in a supportive learning environment. Supportive learning environments promote connection and success, and enable students to thrive. While high potential and gifted students are no different from other students in this respect, they may experience specific social challenges related to their advanced ability and development.

A learning environment where personal best, growth, high achievement and advanced learning are supported and celebrated enhances student engagement.

Asynchronous Development

Asynchronous development creates a mismatch between the student’s development within a domain and that of their age cohort. This can result in the ‘forced-choice dilemma’, where students feel they must make a choice between social acceptance and underachievement, or social isolation. This may also cause frustration when students can think of advanced ideas or concepts, such as an idea for a story or an artwork, but their skills are not yet sufficiently developed to achieve their vision. The challenges of asynchronous development can be more profound with students of exceptional ability, for whom the gap between ideas and skills may be even greater. School counsellor/psychologists can provide advice for individual students in relation to this issue.

Perfectionism

Evidence suggests that there is a higher incidence of perfectionism among high potential and gifted students. Some high potential and gifted learners may feel that success should come easily. This may be due to a lack of appropriate challenge in their learning experiences to date.

Learning tasks or assignments that are too easy may also mean that students do not have the opportunity to develop the learning skills or academic resilience required to manage more complex and challenging tasks. These students will require suitable challenges to allow them to develop the learning skills and resilience to manage complex tasks and take risks.

Healthy Perfectionism

Healthy perfectionism refers to those who work towards excellence, without any negative consequences for themselves or others. In fact, healthy perfectionists are often those who:

- are intrinsically motivated and driven to succeed

- use their mistakes to gain greater insight into the achievement of their goals

- accept their mistakes

- see change as a new opportunity

- value setbacks and challenges

- feel worthy no matter how they perform

- see effort as one way of improving.

Some ways to support students can include:

- using role model examples in a student’s area of interest, so they understand that life doesn’t always give them what they expect

- discussing real world examples to highlight the types of behaviours that return positive outcomes

- celebrating achievements and discussing challenges in equal measure

- praising a student’s effort rather than their just their performance

- celebrating personal excellence, rather than making comparisons between students

- pointing out that mistakes are evidence of learning and that experiencing struggle often encourages resilience, persistence and eventual success

- talking about relevant examples from great people in history who often made many mistakes before they accomplished the things they did

- discussing the great inventions we experience in life today, all thanks to those who paved the way in persisting through their failures and mistakes.

While some perfectionist behaviours can be helpful for growth and achievement, others can be a concern if they begin to interfere with learning and wellbeing in a maladaptive way.

Unhealthy or maladaptive perfectionism

Some high potential and gifted students have little tolerance for making mistakes. They may show great distress when they make a mistake or when others are making mistakes. Frustration, procrastination or anger can be the result.

These are all examples of unhealthy or maladaptive perfectionism. Unhealthy perfectionists act and think in ways that inhibit their progress and impact their wellbeing and self-perception.

Discussing the symptoms and causes of unhealthy perfectionism may help students understand it better. Both teachers and parents should communicate the signs of unhealthy perfectionism which may result in negative consequences.

Sometimes perfectionism can be masked as underachievement. These students may:

- simply stop trying

- always take the safe option

- refuse to take risks or try anything difficult or new

- rarely complete a task

- demonstrate a fear of failure or a blow to their self-worth

- use the excuse that they work better under pressure

- avoid voicing their ideas

- question their own judgement

- avoid change

- avoid close relationships for fear of disappointment.

Schools should support the social and emotional development of their high potential and gifted students as they would all students.

The principles of the Wellbeing Framework apply.