Travel training for students

Travel education can begin at an early age with basic safety rules used by families.

Travelling in the car with appropriate use of seatbelts, waiting and taking turns during a shopping trip, or using buses with family are all valuable opportunities to learn important safe travel skills.

These skills are reinforced in government road safety programs and personalised support programs for students in schools.

A whole-school approach to road safety education is where schools, parents, carers and communities work together to create a supportive environment for students to learn, understand and practice road safety.

At school, early travel skills are a mix of classroom activities such as recognising road signs, reading, number recognition, social skills, verbal skills, problem solving as well as practical group experiences such as excursions and community access.

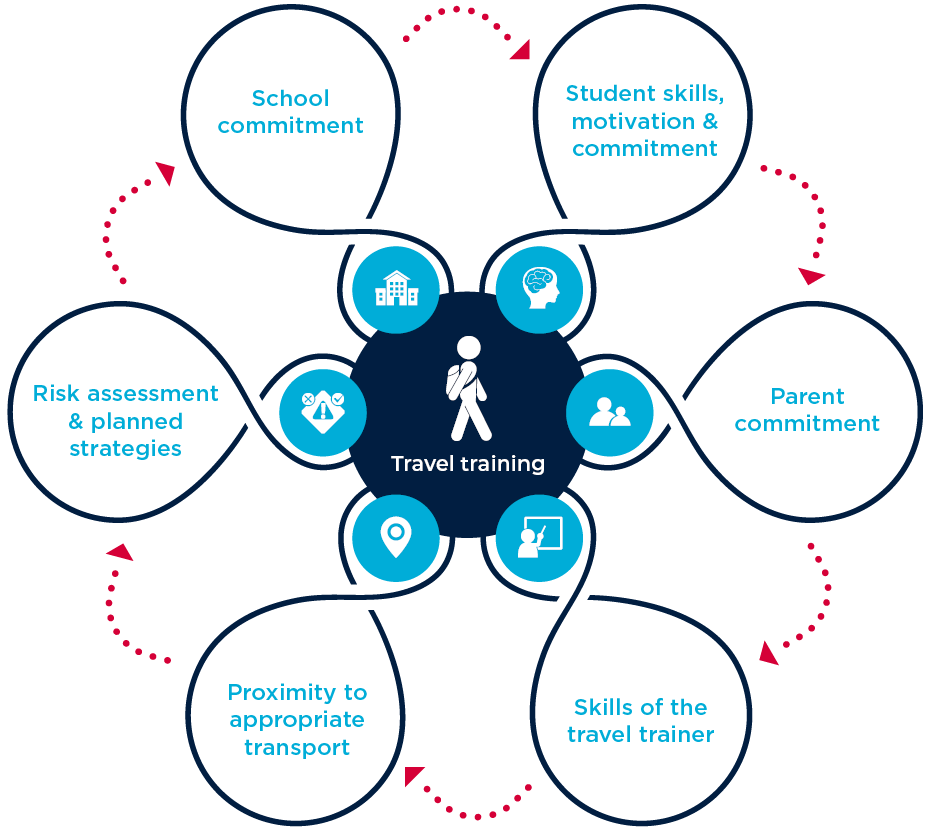

A quality travel training program depends on:

Travel training is one-to-one, short term, individually designed instruction in the skills and behaviours necessary for independent and safe travel on public transport.

Training is provided to students to equip them with the skills to go from the starting point of the trip to the destination and back.

In the schools context, travel training refers to travel between home and school.

Travel training is aimed at helping students to use public transport on their own. Parents can speak with their child's teacher about incorporating travel training into their child's curriculum plan.

Travel training is taught by a trainer who has the knowledge and skills to assess, plan, teach and monitor a travel training program, in the community, for a student with disability.

The benefits of travel training are long term as the training often results in lifelong changes in behaviour among learners. This is one of the reasons why travel training is most effective when received before adulthood, in order to maximise the long-term benefits. — UK Department for Transport

Travel education and training gives students independence and valuable lifelong skills beyond school, including the ability to travel to employment, further education and social events.

As a result of travel training, students may experience:

- increased independence, confidence and self-esteem

- improved engagement at school and improved educational outcomes

- increased opportunities to access employment and further education

- increased opportunities to participate in social and leisure activities

- an opportunity to initiate valuable programs that move the student towards independence post school

- reduced responsibility and an opportunity to move their child towards independence

- increased trust and confidence in their child’s ability to learn new skills.

Schools may experience an opportunity to initiate valuable programs that guide the student towards independence beyond the school environment.

Parents may experience:

- reduced responsibility and an opportunity to transition their child towards independence

- increased trust and confidence in their child's ability to learn new skills

Parents may need support and assistance from the school to understand the program and see that the long-term benefits for their child outweigh any immediate reservations they may have.

While travel training towards independence is not a goal for every student, many primary aged and secondary aged students with disability will reach independence.

Students can be recommended for a travel training program to and from school by:

- parents and carers

- teachers or

- the student themselves.

A functional assessments of student's skills will be needed. Skill areas to be assessed prior to entering a program could include:

- reading and numeracy

- language, and communication

- social/emotional

- problem solving

- behaviour

- health care

- attendance

- their personal and cultural context.

There is a clear need for close consultation and collaboration between the school, the trainer and parents/caregivers, particularly when travel training is initially proposed and as travel training progresses, and monitoring/evaluation of the program to ensure success.

The referral process or initial assessments may indicate that travel training is not appropriate for the student at that time. In such instances, there should be a review plan in place to reconsider potential students as circumstances change or at key milestones in the future.

Journey planning could include:

- investigating possible school routes that are accessible and realistic such as using a current school or public bus

- a formal and thorough risk assessment of the route. This must take place to identify all reasonable foreseeable risks of injury and to consider how these risks might be minimised.

- consultation with the local transport provider

- specific details of the route including road crossing, bus number and time

- organising an Opal card or other travel card requirements

- deciding where to start training – from home to school, or school to home

- deciding to train for part of the week or every day.

It is also appropriate to develop an environmental risk register (refer to the Resources section below) of possible unexpected events during the journey which the student will need to manage. Strategies for these are also included in the training.

For each student participating in the practical component of travel training, a formal and thorough risk assessment must take place to identify all reasonably foreseeable risks of injury and to consider how these risks might be minimised. External service providers, schools, carer and students can be involved in these processes.

Duty of care

Where travel training is provided by an external agency, NSW public schools need to be aware that duty of care rests with the school.

Public schools should refer to the workplace learning procedures and standards and the workplace learning for secondary students in government schools policy for more information on using a private or community registered training organisation.

The school needs to manage the potential risks associated with running the travel training program, as part of discharging its duty of care to students.

This duty requires that schools take reasonable steps to reduce the risk of reasonably foreseeable injury.

While risk can never be entirely eliminated, it can be mitigated through thorough appropriate risk identification and assessment and the development of well-planned, documented and monitored risk mitigating strategies.

Many students can acquire and maintain skills necessary to travel to and/or from school independently.

Discussions about when to start independent travel training are often part of the students' transition planning from Year 5 to Year 7, or from secondary school to post school.

The student needs to:

- demonstrate enough aptitude, motivation, knowledge, mobility and skill to respond to a program of travel training in order to travel to and/or from school

- demonstrate an understanding of routines and can understand and follow the instructions required to either walk or travel to and from school using public transport

- demonstrate the literacy/numeracy/social and emotional skills required for the time and travel requirements involved

- demonstrate the ability to use clearly understandable forms of communication (this may be verbal, written or any other form of communication system) including the ability to learn to use a mobile phone or other appropriate technology

- be able to physically access the required mode of transport.

Discussions could also include the:

- role of parents and the school in teaching skills

- resources needed, such as funding, Opal card, student ID card, mobile phone, emergency contact card, apps, visual supports (e.g. photos of the route on the mobile phone)

- best school term to begin.

Given the diversity in the needs and abilities of students, travel training is most often carried out using a one-to-one approach, allowing the training to be personalised for each student.

Travel training can vary greatly in terms of:

- how the training is delivered

- who delivers the training

- length of the training program

- the focus of training

- the methods and techniques used by the travel trainer.

Travel trainers use the information from all the assessments, including meetings with parents, and teachers (if using a non-school based trainer) to develop a travel training program.

Travel trainers need:

- knowledge and experience in planning for students who are referred for travel training including making adjustments

- to be able to break a skill down into smaller, teachable steps – known as a task analysis

- skills in a variety of assessment methods and using the results to plan and monitor a training program

- the ability to communicate and collaborate well with parent/carers and school staff.

- to be able to motivate students

- enthusiasm, people skills and the ability to mentor others.

Decisions about the overall travel training process could also include the:

- role of parents

- role of the class teacher and the school

- role of outside providers

- funding sources such as the NDIS, school funds, parents and community groups.

A quality travel training program depends on:

Student

Travel training is a learner-centred training process, with the goal of promoting independent and safe use of public transport.

School commitment

Teachers and school staff commit to work/plan collaboratively with students, parents, specialist support staff and transport providers to address individual student needs.

Planning needs to carefully consider the local resources available for the student/family/school and community. This might include practical and human resources such as local transport companies and disability service providers.

Student's skills, motivation and commitment

Successful travel training requires a practical assessment of skills, motivation and commitment.

Parent commitment

An essential element for successful travel training. Parent queries and concerns should be anticipated, respected, and prepared for, school staff and trainers need to obtain parent cooperation and consent before starting a group or individual training program.

Travel training can be promoted to parents through newsletters, individual planning meetings with teachers and school open or transition days.

Skill and selection of the trainer

Knowledge, communication, enthusiasm, problem solving skills and the ability to make adjustments for students with disability are important attributes in selecting a travel trainer.

Proximity to appropriate transport

Consider the local public/community transport options available and their location to the student's home/school.

Risk assessment and planned strategies to minimise risk

Well thought out planning is the key to success in travel training.

Trainers develop personalised plans for students and part of this planning may include observation checklists or a 'task analysis' for students learning new skills.

Prompting sequences with tasks work on a most-to-least approach and they are a valuable way of assessing skill mastery.

Some examples of prompt codes are listed below. For more detailed examples of observation and competency checklist please refer to the Resources section below.

Please note a trainer would need to decide how long to wait between prompts as part of a student's individual travel training plan.

Sample travel training tasks

- Identify and navigate route for bus/train

- Walk safely to bus/train station. Crossing safely at the following points: normal street corners/roads, pedestrian crossings, traffic lights

- Opal card ready for bus arrival

- Can identify bus/train number

- Use Opal top-up machine at station

- Ask for assistance from the appropriate person in a clear loud voice and tell the destination they are going

- Act safely, maturely and appropriately on public transport

- Identify stop and disembark locations

- Navigate return route home.

Examples of levels of prompting when assessing and teaching travel skills

0 = No assistance/fully independent

1 = Indirect verbal prompt/instruction

2 = Gestural prompt

3 = Direct verbal prompt/instruction

4 = Modelling prompt

5 = Minimal physical prompt

6 = Full physical prompt

7 = Unsuccessful trial

N/A = Not applicable

P = Physical prompt

V = verbal prompt

G/M/V = Gesture/model/visual prompt

+ = Independent

CA = Competent, NYC = Not yet competent, P = prompting – verbal or physical