And the winner is ... public education

On the 20th anniversary of the 2000 Sydney Olympics, our staff reflect on the role NSW Education played in making “the best Games ever”, writes Dani Cooper.

15 September 2020

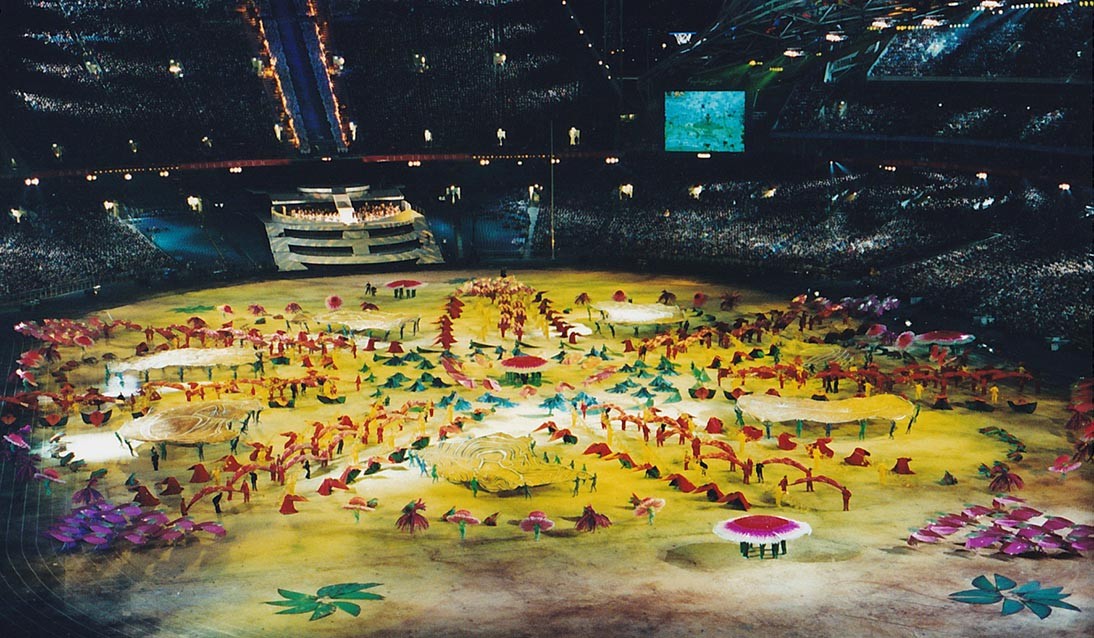

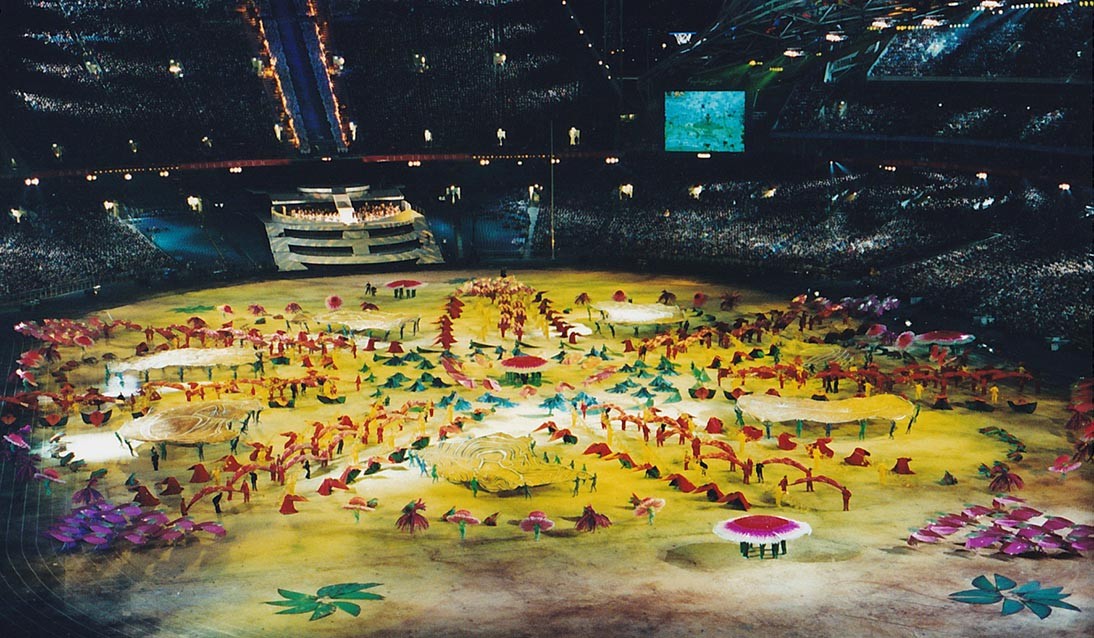

When the world tuned into Sydney for the Opening Ceremony of the 2000 Olympics on September 15, 2000, NSW public education was also on display.

From the successful 1993 bid for the Games to key events during the Olympics, staff and students from government schools were ever-present.

Not to mention the public-school alumni competing in the Olympics and Paralympics, including the Games’ most successful athlete Ian Thorpe and Paralympian Kurt Fearnley, who finessed their skills in NSW public school sports.

Twenty years later and some of the key teachers involved in the September 2000 Games say it remains an unforgettable experience.

Arts Unit head John Benson was then Instrumental Music Coordinator with the Arts Unit and found himself chaperoning public school student choir members in seats beneath the cauldron lit by Cathy Freeman on Opening Ceremony night.

“The students loved every bit of it,” he says. “There was such a buzz and everyone was so excited.”

Teacher Lindsay Frost was also part of the opening event conducting students in the Millennium Marching Band – 2,000 students from across the globe brought together for the Games – and was part of the fanfare trumpeters that played alongside trumpeter James Morrison for the opening fanfare and national anthem.

“It was an amazing experience. I’ll never forget walking out and the goodwill that came from the audience,” he says.

Frost says the input of NSW Education staff should not be underestimated.

“The Arts Unit was critical in facilitating the involvement of students, regardless of which education sector they were a part of, and it’s a resource that NSW Education should be particularly proud to have,” he says.

As part of his involvement in forming a public schools’ marching band, Frost spent two weeks before the Games in Bathurst rehearsing as the bands were brought together for the first time.

“Bathurst was known as bandtown for two weeks and all the secrecy around the band was lost because we were all over the town,” he says.

“Bathurst was cold and wet and freezing … and during rehearsals the band members were standing in the cold for three hours going nowhere but the kids were amazing. They got what it was all about and the only live music in the Opening Ceremony was performed by the marching band,” he adds proudly.

Ian Jefferson, then a casual teacher at Strathfield South Public School, found himself caught in Groundhog Day after agreeing to help coordinate student participation for the Team Welcome Ceremonies at the Olympic Village.

As each team of athletes arrived in the two weeks in the lead-up to the Games, around 160 students from different primary schools were bussed in to sing the Australian anthem and the Olympic song, ‘G’Day G’Day’ as part of a welcoming ceremony.

Although he did meet Nelson Mandela as part of the South African team welcome, Jefferson admits to still being traumatised by the experience as the welcoming ceremony was held seven times each day.

He says the official protocol team had no idea how to deal with kids en masse and the Arts Unit stage crew managing the event had to deal with issues including students vomiting, fainting and toilet accidents.

“I couldn’t wait for it to finish at the time,” he admits. “So much so I turned down tickets to the Opening Ceremony rehearsal, which I later regretted.”

Education’s role in the lead-up to the Games

Former Sports Unit head Ross Morrison says NSW Education’s involvement in the 2000 Games was not just centred on the actual event.

Instead the department was deeply embedded in the bidding process when public schools “adopted” an International Olympic Committee member as part of lobbying activities.

When these members visited Sydney to assess the bid, students from the school met them at the airport, welcoming them by singing their national anthem and then continued to lobby the IOC members by mail on their return home.

Included in the Australian bid was a schools’ education program so integral to the bid’s success that when IOC President Juan Antonio Samaranch announced Sydney’s had won, among the Australian bid team in Monte Carlo was then Sports Unit head Helen Brownlee and a couple of NSW public school students.

Back in Homebush more than 500 students were also gathered alongside officials for the 4.27am announcement with instructions, says former teacher Maureen Stevens, to cheer whether Sydney won or lost.

With the Games secured, Brownlee went on to work with the Sydney Organising Committee for the Olympic Games (SOCOG) and, among a number of groundbreaking firsts in her career, later became the first woman vice-president of the Australian Olympic Committee.

In the lead-up to the Games, NSW Education also played a key role in testing the Olympic site as the host of the Pacific School Games – an international event involving 36 countries and 4,100 athletes between April 31 and May 7, 2000.

It was also the first games to include athletes of mixed abilities – as a tester for the Sydney Paralympics – and that innovation has since been adopted internationally.

Morrison says a crowd of around 75,000 people attended the Pacific Games Opening Ceremony.

It was a major test of the transport infrastructure around Homebush and its success gave the government confidence Sydney traffic would handle the Games disruptions.

The Arts Unit ran the Pacific School Games Opening Ceremony with live student choirs, orchestras and bands.

“We had a dedicated team running the logistics of the event,” recalls Benson, adding that many of those staff were then seconded to work behind the scenes at the 2000 Games.

“There was a huge amount learned during the school games that helped make the 2000 Olympics successful.”

Stevens, who helped co-ordinate the school choirs for the Opening and Closing ceremonies, remembers a focus on secrecy.

"We were involved in what felt like covert operations bringing students from across the state to airfields and huge sheds for rehearsals,” she says.

Stevens says around 500 students were bussed in weekly for 10 weeks for the Games rehearsals. In a time before mobile phones were ubiquitous, a bus would leave Murwillumbah on the far north coast at 3am and pick up students and their accompanying staff along the way to Sydney.

“We just had to rely on students to be there. We had buses coming in from Grenfell, Armidale, Orange and down and up the coast,” Stevens said.

“And then at the end of the day we had to reverse it all and send them home, all with a paper note about the next week’s rehearsal.”

And then it was Show Time

Beside the 500-strong choir underneath the cauldron in the Olympics Opening Ceremony, another 700 students from Sing 2001 were in the show, a further 100 were involved in the closing ceremony and a 2,000-strong student choir took part in the Paralympics Opening Ceremony.

“The logistics were phenomenal and we relied on incredibly dedicated teachers to do all the coordinating,” she says.

“There was a lot of emotional and physical effort – SOCOG wasn’t easy to work with and didn’t understand what we were doing ... they would change details and we would have 500 kids already on buses headed to Sydney.”

The pressure was such that Stevens says she “couldn’t bear to watch the Opening Ceremony when it was replayed on television at the end of the Games.”

Benson says the work done by staff and teachers had a lasting impact and legacy. Stevens agrees and says the Olympics experience gave her newfound confidence in what teachers could achieve and pushed her forward into new career paths.

Frost says a lot of students in the marching band went on to work for the department and the marching band continues today as the NSW Public Schools Millennium Marching Band.

“The best part of the whole opening ceremony was the [marching band] program kept going ... it was put together for that one purpose but lives on,” says Frost.

- News