Step 3: Design the questionnaire

Surveys can collect a mix of quantitative and qualitative data, depending on the nature of the questions you ask and how you analyse the data.

Types of survey questions: closed vs open

Closed questions ask respondents to choose from a limited number of pre-written response options or provide a very simple answer. They are usually quick and easy to answer, and provide quantitative data. There are several different types of closed questions, including:

- single choice lists (identifying a school from a list, for example)

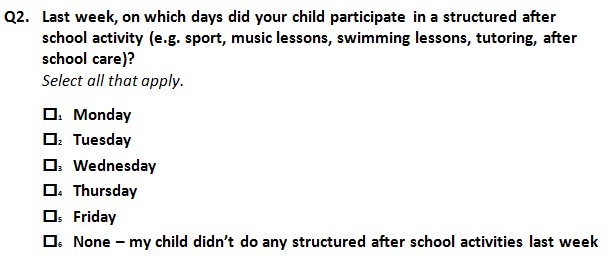

- multiple choice lists (where respondents can ‘select all that apply’)

- numeric answers (year of birth or age, for example – drop-down boxes are good for this, if online)

- binary scales (‘yes’ or ‘no’; ‘true’ or ‘false’ etc.)

- multi-point rating scales (‘excellent’, ‘good’, ‘fair’ and ‘poor’, for example)

- ranking (usually in order of priority or preference).

Open questions ask for a free-text response, where respondents can express their views or experiences in their own words. Common uses include:

- Asking people to describe the ‘best thing’ or ‘worst thing’ about an exercise they have participated in, or asking for suggestions about how something could be improved.

- Following a closed question with a clarifying open-ended question, to seek an explanation for their answer. For example, a closed scale question along the lines of ‘How satisfied are you with X’ can be followed up with the open-ended question ‘Why do you say that?’.

- When offering the option of ‘Other’ in a list, asking people to specify what they mean. Open questions provide qualitative data: rich in descriptive detail but time-consuming to analyse. Responses to open-ended questions can be coded as part of the qualitative analysis, allowing us to understand (for example) which issues were more common, and who tended to raise what. (Follow the link below to Step 5: Organise and analyse the data for more.)

How many questions?

The main measure of survey length is not the number of questions, but the amount of time it takes to answer them.

The overall goal for questionnaire length is to use people’s time well, focusing just on information we need and questions that are clear and relevant to the respondent. You need to avoid the temptation of asking all the questions you can think of, or ‘going fishing’ with a large number of open-ended questions. The longer your survey takes to complete, the greater the risk of non-completion or people skim-reading your questions and giving superficial answers.

The optimum survey length depends on the format (follow the link below to Step 2: Choose a survey format) :

- Hard-copy surveys are normally limited by page length – short surveys on 1-2 pages, longer surveys taking 4-6 pages.

- An online survey should take no longer than 12-15 minutes to complete – shorter if possible.

- A face-to-face intercept survey should only take a few minutes.

Tips for developing a quality questionnaire

- Clearly identify the purpose of the survey in the evaluation before writing the questionnaire.

- Make the purpose of the survey clear to the respondents.

- Only ask a question if the data is unavailable from somewhere else.

- Focus each question on a single point, never covering more than one issue or idea. For example, consider the question: ‘To what extent does current funding cover professional learning and student wellbeing needs?’. This is a double-barrelled question, and should be split into two: one question about the coverage of professional learning; another about coverage of student wellbeing needs.

- Try copying each question out of the draft questionnaire and pasting it into the report structure. If it’s not clear where the results from a question would be reported, then either the report structure isn’t well aligned with the purpose of the evaluation or the question isn’t that important after all.

- Use simple, natural, conversational language that participants will understand and feel comfortable responding to.

- Ensure that all response options for a question stem begin with the same grammatical structure.

- Keep questions neutral, so as not to lead the response down a particular path. For example: ‘Why do you like working at this school?’ assumes that the respondent likes working at the school, and gives no alternative. A better option would be ‘What do you like about working at this school?’, as this allows the respondent to cite specific examples or none at all. Better still would be asking the opposite question directly afterwards, or even side-by-side on the page ( ‘What do you dislike about working at your school?’ ), as this highlights the desire for balance.

- Ensure that the questionnaire has a logical, conversational flow.

- Ask descriptive questions about people’s experiences first, before directing them to questions about the experiences they have had. This kind of ‘flow control’ is easier to achieve with online surveys than on paper.

Grid formats are where each row is another statement or item, and each column is a response option (for example, ‘Excellent’, ‘Good’, ‘Fair’, ‘Poor’).

- In paper surveys, where space on the page is limited, small grids with up to four or five items are acceptable.

- In online surveys, avoid grids and just present each question one after the other. This is better for respondents’ attention to the questions and avoids skim-reading and disengagement with the task.

- In online surveys, we can expect around one-third of respondents to complete the survey on a mobile phone, rather than on a full screen computer. Most survey hosting programs convert grids to item-by-item presentation automatically when they are being completed on a mobile phone or other small screen device.

- When framing questions that require reference to memory, specify a timeframe ( for example, ‘In the last three months…’ ) or a place ( for example, ‘When you are in the staffroom…’ ).

- When asking people to select one option from a list, make sure the categories are mutually exclusive (for example, ‘under 18’, ‘18-29’, ‘30-39’, ‘40-49’, and so on).

- In online surveys, make all closed questions compulsory. If it’s a sensitive issue, offer a ‘Prefer not to say’ option.

- Offer ‘Not applicable’, ‘Not sure’, ‘None of the above’ or ‘Other’ response options when necessary. Forcing people to guess or choose an option that doesn’t match with their experience will frustrate them, leading to inaccurate data and non-completion.

- In online surveys, we can minimise use of ‘Not applicable’, ‘Not sure’ and ‘None of the above’ by using good flow control. This is where the first question in a set establishes the respondent’s eligibility to be asked the other questions in the rest of that set.

- Scales should use natural, conversational language to describe the categories. For example, when asking about teachers’ confidence with a certain practice, our response options might be: ‘I wouldn’t know where to start’, ‘I’d appreciate a bit of support with this’, ‘I could do this unassisted’, and ‘I could assist others with this’.

- There is no ‘magic number’ of points on a scale. Scales should have as many points as you need in order to reflect the range of positions that people might take on an issue.

- Scales do not necessarily have to be ‘balanced’ or symmetrical in order to be valid. For example, it might be entirely appropriate to give response options of ‘Yes, always’, ‘Yes, sometimes’ and ‘No’.

- ‘Unipolar’ scales start at a natural zero point and then go to an extreme. Two examples are scales relating to frequency (‘Never’ to ‘Always’, for example) and quantity (such as ‘None’ to ‘More than X’). For consistency, unipolar scales should be displayed with the smallest at the top of the list or the left hand side a grid, through to the largest at the bottom or right.

- ‘Bipolar’ scales go between opposites, often through a neutral zero point. One common example is the Likert scale, which runs from ‘Strongly support’ to ‘Strongly oppose’, through a mid-point of ‘Neither support nor oppose’. Other examples include satisfaction scales (‘Very satisfied’ to ‘Very dissatisfied’) and Agree-Disagree scales (a common variant of the Likert scale).

Agree-Disagree scales are commonly used, but can be difficult for participants to interpret and in analysis. A better option is to use response options that are specific to the construct being measured.

Example 1: Someone thinks the food at the conference was incredible – the best they’ve ever eaten. The statement on the feedback form is ‘The food was good’. Do they select ‘Strongly agree’? Or do they ‘Disagree’, because it wasn’t just good – it was amazing? A better option for the feedback form would be ‘How would you rate the quality of the food?’, with a scale that goes from ‘Excellent’ to ‘Poor’.

Example 2: Someone disagrees with the statement ‘The level of detail in the course was appropriate for me’. Why did they disagree? Was it that the course was too detailed, or that it was not detailed enough?A better option for the feedback form would be posing the question as a sentence completion: ‘The content was…’ with response options ‘Too detailed’, ‘About right’ and ‘Not detailed enough’.

Midpoints in scales should only be used if the construct itself has a midpoint.

- Unipolar scales (see above) have no natural mid-point.

- With bipolar constructs (see above), some need a midpoint. For example, an assessment of perceived change might run from ‘Much better’ to ‘Much worse’, with ‘No difference’ as the natural zero point in the middle.

- Some bipolar constructs do not lend themselves to a midpoint. For example, we would never naturally describe ourselves as feeling ‘Neither clear nor unclear’ about what is expected of us even though the extremes of feeling ‘Very clear’ and ‘Very unclear’ are easy to understand.

The option of ‘sitting on the fence’ can be removed by choosing a scale that does not need a neutral option. One good example is a four-point scale based on the word stems ‘Very…’, ‘Fairly…’ ‘Not particularly…’ and ‘Not … at all’ (for example, ‘Very clear’, ‘Fairly clear’, ‘Not particularly clear’ and ‘Not clear at all’).

If offering a ‘Don’t know’ or ‘Can’t remember’ option, place this at the end of the list (not in the middle, as it is not a midpoint).

In online surveys, put each question or small set of questions on its own screen. Responses are captured and stored on the server every time the respondent clicks ‘Next’.

Even the most experienced survey researchers pilot their survey instruments to fine tune them before putting them into the field. Testing a survey will provide feedback on:

- whether the questions are interpreted by respondents as intended

- whether the response categories are appropriate, and will provide enough data to analyse

- the functionality and flow of the survey experience.