Kempsey honoured as birthplace of public education

As we celebrate Education Week and 175 years of public education, Linda Doherty shares how our history has shaped today’s school system.

31 July 2023

Two years before convict transportation to the Colony of New South Wales was abolished, a public notice was posted in the tiny settlement of Kempsey on Dunghutti Country.

“A Public Meeting will be holden at the Bush Inn Kempsey on Monday the 24th of April next for the purpose of taking into consideration the best mode of establishing a school in Lord Stanley’s National System . . . John Simpson, Kempsey 12th April 1848.”

The notice sought support to establish a school for local children based on the Irish National System of state-regulated, secular education introduced by Chief Secretary Edward StanleyExternal link.

The Kempsey families made an application to the Board of National Education, appointed by New South Wales Governor Charles FitzRoy to fund and run the first government schools in Australia.

Five months later, on 23 September 1848, Kempsey National School opened – the first public school to be established in Australia, welcoming students of all socioeconomic circumstances and religious faiths. Before 1848 schools in Australia were operated by churches or charities.

Kempsey’s place in history as the birthplace of public education is proudly acknowledged in the mid-north coast town of 30,000 people where almost 13 per cent of residents are Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander peoples.

“It’s such an honour for our schools, students, staff and communities to celebrate this historic milestone where public education began 175 years ago,” said Emma Jeffery, Director, Educational Leadership for the Macleay Valley Network of schools.

“Today there are 15 public schools in Kempsey and its surrounding villages, and each school adds something special to the vibrant and close-knit communities.”

The local schools will celebrate Education Week with a variety of events, including the Macleay Valley Public Schools Music Festival at Melville High School tomorrow.

Education Week 2023 celebrates 175 years of public education, focusing on learning from the past, celebrating achievements and embracing the future with confidence.

NSW Education Department Secretary Murat Dizdar said public education emphasised equity and inclusion as core values.

“All students, regardless of their postcode and life circumstances, deserve the same opportunities,” he said.

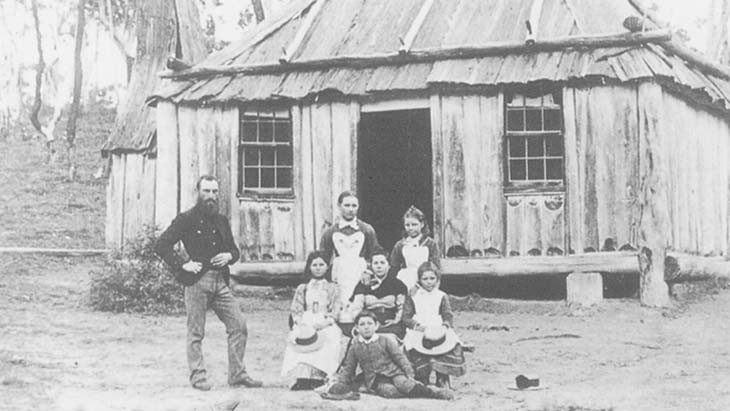

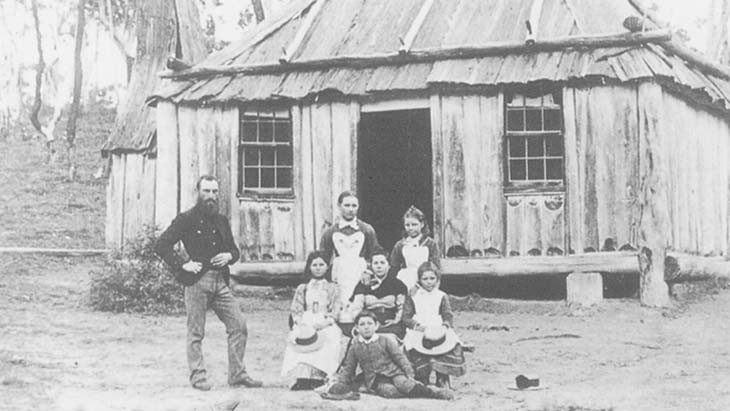

“The history of public education reflects the development of our State, from the slab hut schoolhouses in the Colony of New South Wales, where parents paid for teachers, to the free and state-of-the-art schools we now build in high-growth areas in the State.”

The early years

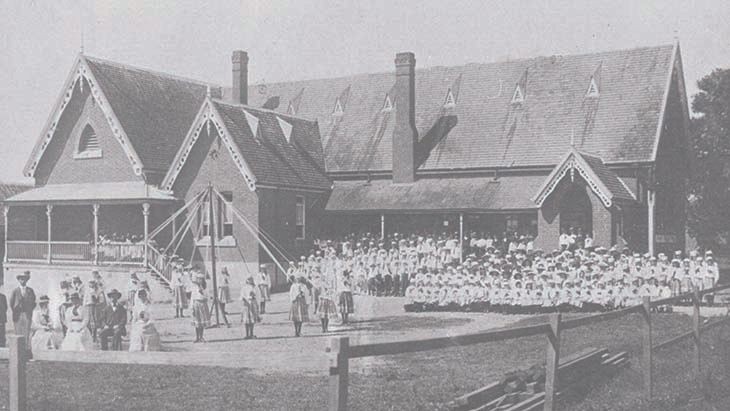

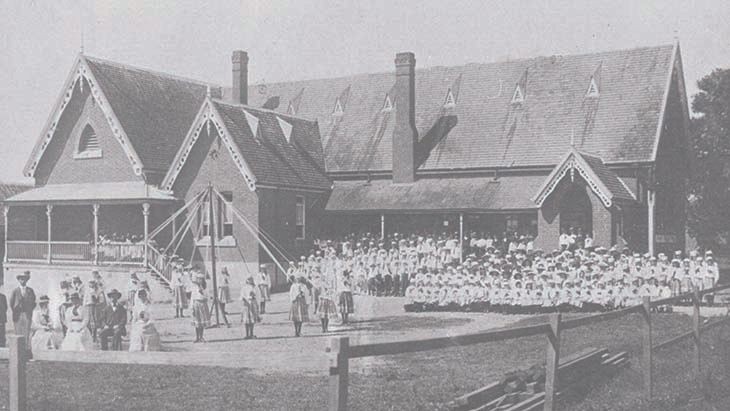

Kempsey National School opened in a wooden schoolhouse with Mr and Mrs Fowler as teachers.

Parents were asked to contribute to the cost of a new building, but the school closed in 1850 “after many local squabbles” and an exodus to the Gold Rush, according to ‘Sydney and the Bush: A Pictorial History of Education in New South Wales’.

Kempsey West Public School, which like many schools has had different names and locations, opened in 1860 as Kempsey National School with 23 boys and 18 girls taught by Thomas Hird and his wife, Elizabeth, in a room behind their general store.

The school’s history includes the disappointment of a teacher, Mr Simpson, when only 13 students attended school in his first week. “This was due to a large flood and students could not come by boat across the river to school.”

In 1882 there were 237 students enrolled at “a very overcrowded school and the Department of Education sent a large tent to act as a classroom” for 90 students.

Most of the early public schools opened in rural settlements where there were no existing church schools.

Parents had to contribute one-third of the school building costs, guarantee attendance of a minimum 30 students and pay school fees, which went towards the teachers’ salaries.

It wasn’t until 1880 when Sir Henry Parkes introduced the Public Instruction Act that compulsory and free education became the norm.

Kempsey National School was the only public school to open in 1848 but 14 more opened the following year.

The next to open were Largs Public School in the Hunter Valley and Botany Public School in Sydney, both in January 1849.

Local historian Jenny Datson can trace five generations of her family to Largs Public School.

“I love the family atmosphere of Largs. The older children take the younger ones under their wing, caring for them and teaching them playground games,” she said.

Botany Public principal Heather Strachan said the school’s history was an integral part of its identity.

“It is important to remember that children and adults have come to this land to connect, learn and play for many hundreds of years, long before Botany Public School opened, and to celebrate this land’s history as both a school and a safe place for Aboriginal people prior to the arrival of the First Fleet,” she said.

Some of the earliest public schools still operating also include Fort Street Public and High School and public primary schools in Albury, Bathurst, Braidwood, Camden, Dungog and Grafton.

By 1851 there were 37 public schools in NSW educating 2,300 students. By 1900 – when there were only a handful of secondary public schools – students typically left school at age 12 to start work.

Today the NSW Department of Education is one of the largest education systems in the world, with 800,000 students learning in 2,200 public schools. The school leaving age is 17 and two-thirds of students finish 13 years of education in Year 12.

The early teachers were largely untrained. Under the legendary educator William Wilkins, appointed as the first headmaster of Fort Street Model School in1851, the Colony introduced the pupil-teacher system where students aged from 13 trained as apprentice teachers in the classroom.

Wilkins’ reforms were adopted by the other National Schools, including the introduction of timetables and classifying students according to age, ability and gender.

“The course of study was extended to drawing, music, geography, scripture, drill and gymnastics,” according to the ‘Australian Dictionary of Biography’External link entry on Wilkins.

“Moral suasion rather than corporal punishment became a feature of school discipline.”

Corporal punishment was finally abolished in NSW public schools in 1987.

Learning from our past

Department Secretary Murat Dizdar today urged all educators to learn from “the policies and practices that have come before us across those 175 years”, particularly policies that discriminated against and excluded Aboriginal students.

“The practice of truth-telling is such an important part of a learning organisation like ours. It's about facing past wrongs and speaking openly about them in the spirit of healing and reconciliation,” Mr Dizdar said at the launch of Education Week at Cambridge Park Public School in western Sydney.

“It shames me that some of our past policies excluded Aboriginal children from attending public education.”

Gamilaraay woman Anne Dennis was born on the Namoi Aboriginal Reserve near Walgett, completed Year 12 at Walgett High School in 1976 and obtained her Bachelor of Education teaching degree from Charles Sturt University.

Ms Dennis, a public education advocate and former teacher, said in an interview for Education Week that education was denied to her parents and grandparents and her own schooling was a type of refuge from “the fear of the welfare” removing Aboriginal children from their families.

Up until 1972 Department of Education policies permitted principals to refuse to enrol Aboriginal students on the grounds of “home conditions” or “substantial community opposition”.

This was almost a century after the Aborigines Protection Board had started setting up segregated Aboriginal reserves outside of towns and establishing mission schools to train children to be domestic servants or farmhands.

The NSW Aboriginal Education Consultative Group Inc (AECG)External link – the Department of Education’s partner in Aboriginal education – records there were 13 ‘Aboriginal’ mission or reserve schools by 1900 and 40 by 1930.

By 1940 the department provided trained teachers for Aboriginal schools and education beyond Grade 3.

Ms Dennis, a former AECG president, said the Department’s policies were exclusionary and ignored the needs of Aboriginal communities until the development of the NSW Aboriginal Education Policy in 1982, the first of its kind in Australia.

Mr Dizdar said the Aboriginal Education Policy today “confirms our deep commitment as a system to improve the educational outcomes and wellbeing and opportunities” for Aboriginal students, as did the department’s partnership agreement with the AECG.

“I’m enormously proud of our partnership agreement . . . It implores us to ensure that every Aboriginal child and young person in NSW achieves their full potential in education,” he said.

- Public schools in Kempsey and the Macleay Valley: Melville and Kempsey High Schools; and primary schools Aldavilla, Bellbrook, Crescent Head, Frederickton, Gladstone, Green Hill, Kempsey East, Kempsey South, Kempsey West, Kinchela, Smithtown, South West Rocks and Willawarrin.

The oldest continuously operating school

Newcastle East Public School was educating students well before the first public school opened.

The school started as a charity school inside a church vestry in 1816, under instructions from Governor Lachlan Macquarie, to provide free education to the children of free settlers and convicts.

Henry Wrensford, a convict on a conditional pardon, was the first teacher and educated 17 convict children aged from three to 13 years.

Newcastle East Public School is officially Australia’s oldest continuously operating school and joined the NSW public education system in 1883.

Principal Mick McCann joined the school in 2016 in its bicentennial year.

“Newcastle East Public School has a long, proud and important history. Our school has been the heart of our local community for more than 200 years,” he said.

“We are thrilled to promote Education Week as an annual event and as an ongoing commitment to our students' development and success.

“We believe in fostering a culture of continuous learning and growth.”

The school celebrates students’ achievements, talents and hard work with regular showcase assemblies.

“These events are enthusiastically attended by our supportive parent community who take pride in witnessing their children’s achievements,” Mr McCann said.

- News

- 175 years